1st Day, 1st Ride, 9th Month, 1374th Year

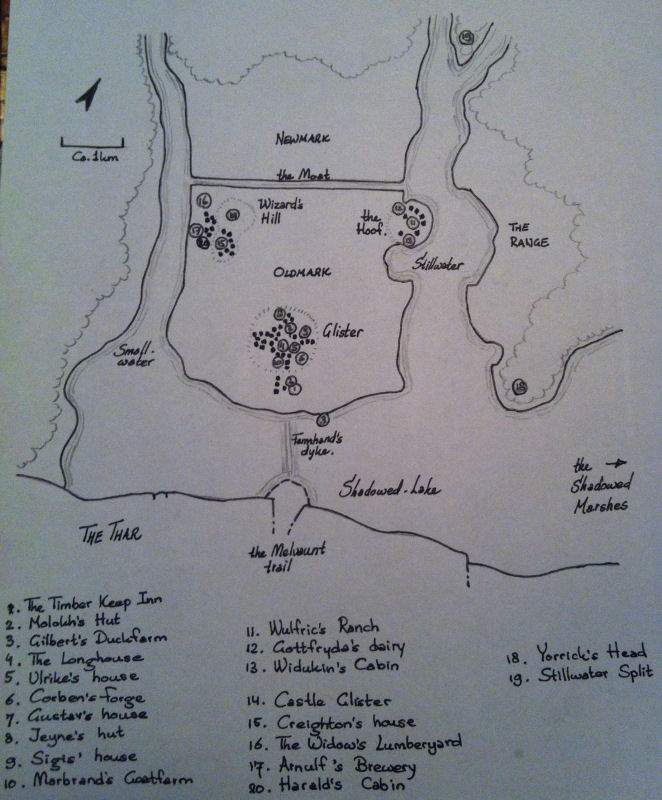

It has been two years since the battle with Nar-Narg-Naroth. Much has changed on the Oldmark. The new Lord of Glister has shaped up the militia and has built a palisade along the moat, further separating the Oldmark from the Newmark. Harald has been replaced by Widukin as the paragon of the foresters and he has been working in concert with Jago to open up new and secure old trade routes.

The village has grown and its productivity has grown along with it. I’ve helped optimise the production of arable land by changing crop rotation cycles and fine tuning sowing and reaping times. I am loathed to take responsibility for the jump in crop yield. The herds of cattle on the Hoof have also been procreating faster and more steadily, and growing larger and healthier than before. I suspect that vanquishing the Tanar’ri has had a positive effect on Glister. And dare I say on the whole of the Thar.

I’ve been…reckless with my divinations, but I cannot say it’s been without its rewards. If it wasn’t for the current unrest in Glister I would spend much more time learning the secrets of the bloodstone, and the being that is banished inside of it.

Quentyn has made great strides in advancing himself as the Lord of Glister. He has also made great strides in advancing Glister as a trading hub along the Thar. Neighbouring fiefdoms have sent word, and a certain Lord Balta, the Western Warden of Vaasa even made the trek to Glister to make a personal appearance.

Occasionally there is word from Cormyr. A great horde of orcs has descended upon my homeland. I’m certain that the Cormyrian knights and war wizards are more than capable of defeating the horde — it is not the first time they come reaving down from the mountains — but I cannot help but be somewhat worried for my family. Danan especially. He should be of an age now that he’ll have his own command, or leading some vanguard. I wonder if he’s been anointed yet. I should write him again. Until I hear back, I shall pray to Chauntea to lend strength to him so he can defend home and hearth.

As a result of the trouble in Cormyr, and likely eager to send word back of his progress, Quentyn has send an open invitation for refugees to come and settle in Glister. His ambition is admirable. For a long while I thought that none would make the trek across all the way north to Glister. Even if you take a boat across the Sea of Fallen Stars and north into the Moonsea, like I did, the journey across the Thar from Thentia, Melvaunt or Hulburg will take weeks.

And yet, they came. A large host of sixty mercenaries, lead by a Cormyrian knight by the name of Ser Fosco. It was a ragtag band of Cormyrians, Sembians, and mongrels. Glister was ill-prepared. Quentyn was ill-prepared. I am not sure what he was expecting, but I was expecting people less armed with swords and more armed with ploughshares. They look less like settlers and more like raiders. But here they are, looking for a home.

The settlers — yes, settlers, that’s what they are and I will continue to call them that so that they, and the people from Glister, don’t forget why they’re there — have settled in a large camp on the Newmark, just across the moat, in sight of the keep. It’s been weeks now, and understandably they are getting restless. I don’t know what is stopping them from settling properly. I guess my curiosity has gotten to the point where I will set aside my studies and venture forth. Perhaps I can help.

This day I woke up to the smell of food coming from the kitchen. When I came downstairs, I saw that Quentyn joined his two squires — Godric and… and… Godric and the other one — to break their fast. Mund had prepared what most people would consider a fine start of the day. Despite being here for a while, I still have trouble adjusting to the Glisterian choice of food. The Thar breeds hardier people than myself.

Luckily, I’ve been able to figure out what works for me. The friendly simpleton Gilbert and I have grown friendly, and he sells me eggs from his flock of ducks. Mund has started to prepare the eggs in the different ways. When I told him to be more conservative with the spices, his creations became a delight.

The amount of wine in the village is still at an abysmal level. It’s rare. The villagers seem to enjoy their ales and meads more and so the merchants have given up bringing it on their voyages across the Thar. I’ve started to drinking some light ciders, which I’m learning how to digest. If I don’t overdo it, the acidity of the apples doesn’t upset my stomach. Perhaps I should see about getting Jago to bring some grapevines from his trips to Hulburg. Perhaps I can start growing my own. The climate isn’t suited for it, but with Chauntea’s blessing anything I create will be better than ale.

While I quietly ate my breakfast at the kitchen table I started to wonder what kind of knights these two squires would become? They seem brutish, boorish and devoid of the five chivalric virtues that a knight should imbue; valour, honour, compassion, generosity and wisdom. Perhaps I shouldn’t judge them too harshly. Perhaps it’s simply that they don’t come across as any of these things. At the Circle of Magi I had to jump through some awful hoops in order not to be judged too harshly. I ended up showing everyone wrong. I hope Godric and… thinger will show me wrong.

With Quentyn not being a knight himself, or a priest; can he even anoint new knights?

Creighton arrived and joined to break his fast. He asked Quentyn if it was wise that Wulfric dictate the terms of the moot. Apparently, Wulfric had called for a moot. Apparently, the mercena*… no, the settlers had been causing some trouble. Skirmishes, intimidation and thievery had gone up and the settlers had been involved in all instances. Quentyn decided that as lord, he should be the one to call for a moot.

Brother David arrived wearing that ghastly chain of his and heartily attacked the breakfast larders. He had come to ask about the moot as well and he was also able to confirm that the settlers were the cause of much unrest on the Oldmark.

After breakfast brother David wanted to check my constitution. I could have saved him the effort and replied with “miserable,” but he seemed quite insistent. My seizure has left him worried. When the checkup was concluded I was told I was relatively good health, which was good. I was told that I shouldn’t neglect the hearth during my studies. I knew what that meant. Oftentimes I am so lost in thought or study that the hearth extinguishes and the bitter cold creeps into my bones.

We spoke briefly about the settlers and the moot. He wanted us to keep the mood of the moot calm and to prevent the villagers from antagonising the settlers. They are well armed and most of them seem seasoned combat veterans. They could take over the village if they wanted to.

We all met atop the keep to look at the camp of the settlers on the Newmark. We noticed the banner of Ser Fosco; a triangle of three black arrows on a field of green. His heraldry seemed sophisticated enough that he should likely be, or have been, a landed Cormyrian knight. I did not recognise his banner, but I resigned to find out what I could. Perhaps Lord Marbrand left some books on Cormyrian heraldry behind while searching for his heir. I could send Blackwing for Cormyr to inquire, but it would likely take two rides for her to return.

We all ended up walking up to the Hoof to find Wulfric. I was reminded that when we had first arrived in Glister, Wulfric’s daughter Annika had been taken by gnolls. Quentyn, brother David and Jago saved her and Wulfric was very grateful. I wondered what had soured his mood towards Quentyn, and whether we’d have to remind him about the debt he owed them.

I felt embarrassed to find that Wulfric was actually quite hospitable and friendly. He offered us some cheese that his daughter had learned how to make, and essentially confirmed what we had already suspected. He wasn’t happy with the way the settlers had been behaving.

His main gripe, besides the infractions, was that the settlers simply weren’t contributing to the village. They were not producing, only consuming. Not pulling their weight. He also wanted to know where we would house them. And why they seemed so disinterested in clearing land, erecting houses and plowing fields.

Even with the added productivity of the fields and the herds, could we keep up that productivity under the strain of sixty extra mouths to feed? It was a very valid question, but not one I could answer without doing some mathematics first. I decided to talk to Creighton and get to the bottom of that conundrum. How much food is produced on how much arable land? To house, feed and cloth sixty people, how much extra land needs to be tilled, how much extra cattle will it take, how much extra game needs to be hunted and how much extra fish needs to be caught? Once we know that, we know what we’ll need to provide in terms of land, tools, seed and cattle.

Jago and Widukin had joined us at Wulfric’s the moment they heard we were on the Hoof. When we left, we decided to pay a visit to the settler’s camp and Jago decided to join us. We crossed the palisade and took the ferry across the moat and walked up to the camp.

At the camp we were made to wait outside the camp. Under guard. Eventually it became insulting and Quentyn resolutely shouldered his way past the guards. He and I don’t have much in common, and in that moment I was jealous of his ability to command respect simply by imposing his physique and stature. It probably doesn’t hurt that brother David, who is an imposing man himself, was standing to his side wearing that ugly chain and that magical cloak of furs.

Ser Fosco turned out to be a tough nut to crack. There was some back and forth between the knight and Quentyn and it became… tense. It certainly felt as if Ser Fosco was trying to squeeze every bit out of the leverage he had, even if that leverage was gained through intimidation. It became quite clear that Ser Fosco wanted to be a landed knight yet again and I wondered how realistic it was to introduce feudalism to Glister.

A deal was struck; Ser Fosco would keep his settlers in line, Quentyn would come up with a plan and present it at the moot in two days. Quentyn would bring three people, as would Ser Fosco. Quentyn decided to depart, but brother David asked Ser Fosco’s permission to walk the camp and tend to the needs of the settlers. He granted permission, though I felt that permission wasn’t his to grant. The Newmark was as much a part of Glister as the Oldmark, despite being outside the palisade.

While walking the camp with brother David we both came to the conclusion that most of the people in the camp came to Glister to earnestly accept Quentyn’s invitation. Brother David could detect some bad apples in the batch, but most of the Cormyrians really were fleeing the war in our homeland looking for a better life.

We met a priest of Tempus by the name of Gunnar, a wintered soldier. He was open and amicable, and his voice betrayed his Damaran heritage. He wasn’t sure whether he would stay. This made sense to me and confirmed to me that we had gotten the right of it; the majority of the people here came with good intentions. If they would stay and settle, Gunnar would move on to find the next battle, to find another war to serve his Lord.

When we were done we returned to Ser Fosco’s tent. Brother David had asked me to distract Ser Fosco a bit so that he could say a prayer. So I asked Ser Fosco where he was from and how he came to leave. His tale was a tragic one, of a small house of some nobility, losing more and more power when the orc horde came, until all that was left was a title. It seemed Ser Fosco was here to reclaim some of the prestige he lost in the war.

On the way back to the Oldmark, brother David told me that he had divined that Ser Fosco had a deeply selfish core and I was once again reminded of the conversation I had with Quentyn and the two squires; was Ser Fosco an exemplary knight? Did he embody the five chivalric virtues of knighthood?

When we returned to the keep, we talked to Quentyn about what we had found at the camp, and the conclusions that we had drawn. I suggested that we’d refer to the land to be designated as “The Gift.” It would help us in our conversations, and convey the spirit in which we were entering these negotiations. It also sounded good.

Before bed, I talked to Creighton and came up with a plan to do the mathematics about what Glister currently produced in terms of crops, cattle, fishing and game. We would need to come up with several models in which we distributed the sixty new hands in such a way as to optimally create enough goods to support the visitors and yield the most to Glister.