In response to one of my previous posts, A Flick of Hares:

Tag: Language

A Flick of Hares

21 September – A Flick of Hares

There are a few areas of language that get people going quite as much as whether the correct term for a bunch of politicians is a posse or an odium (or worse), while lexicographers have long been looking for their own group name – a sentence (though the judges have already taken that one)? The only boring thing about collective nouns is their name.

The majority of group terms that we know and love today – ‘a gaggle of geese’, ‘an exaltation of larks’, ‘a murmuration of starlings’ – sprang form the medieval imagination. Created by the elite of the elite, they were written down in books of etiquette aimed at instructing the nobility on how not to embarass themselves while out hunting, hawking, or fishing. For the medieval nobleman, knowing that the correct term for a group of ferrets was a ‘busyness’, for hares a ‘flick’, and for hounds a ‘mute’, was a badge of honour. A handling of these terms would not only avoid humiliation, but would mark the gentry out from the peasants.

Our primary source for such terms is the fifteenth-century Book of St Albans, a three-part compendium on aristocratic pursuits. Its authorship is attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, Prioress of the Sopwell nunnery in Hertfordshire. Not only did her work contain over a hundred and sixty group names for beasts of the chase and characters on the medieval stage, but it also boasted the first images to be printed in colour in England. It was an instant hit, reprinted and reissued many times both by William Caxton and the (superbly named) printer and publisher Wynkyn de Worde. Its popularity extended far beyond the nobles for whom it was originally intended.

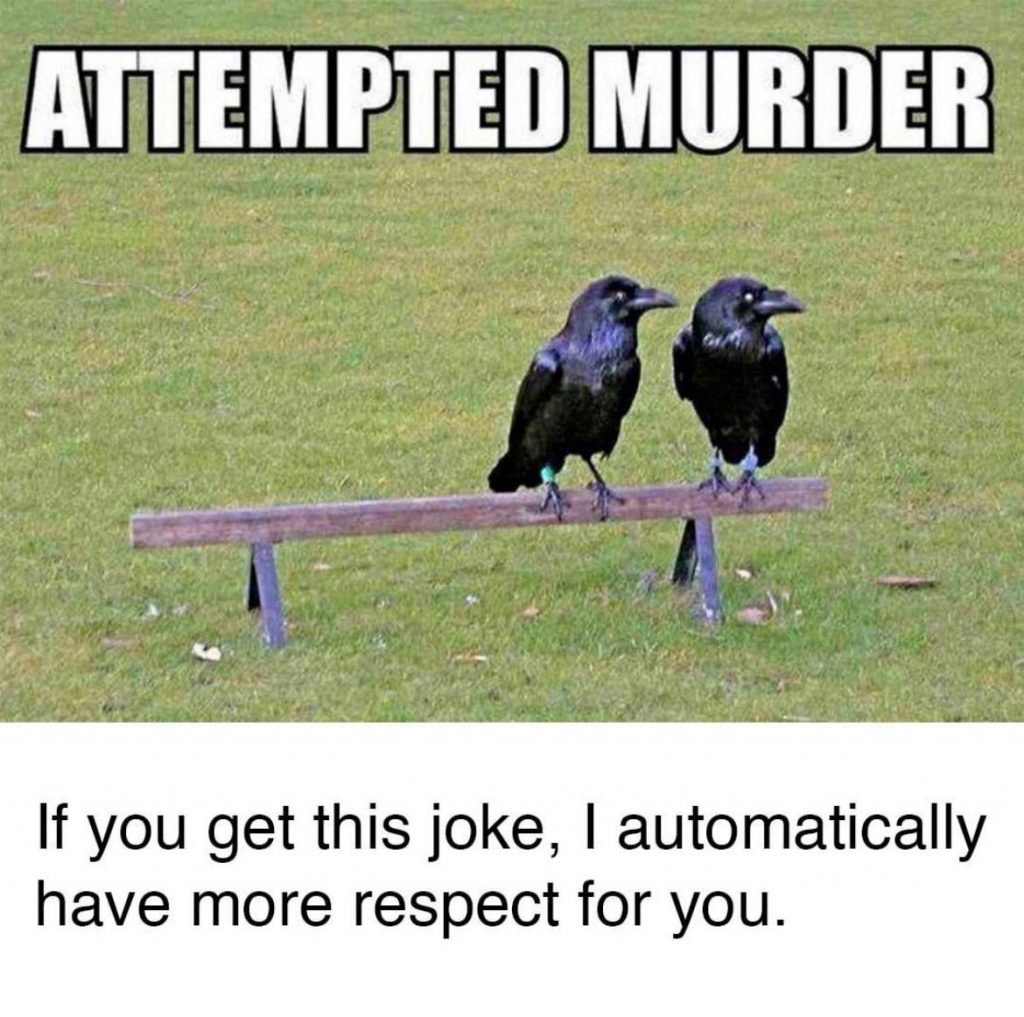

More than half a millennium on, we still use many of these concoctions, relishing the knowledge that congregated crows form a ‘murder’, and that foxes come together in a ‘skulk’. Others among those fifteenth-century lists prove that collective nouns have invited wordplay from the start. You only have to hear ‘an incredulity of cuckolds’ or ‘a misbelief of painters’ (such as portrait artists, who rushed to broaden the shoulders and embellish the eyebrows of their subjects) to eavesdrop on the medieval sense of humour. ‘An abomination of monks’ made fun of those who took solemn religious vows but who were frequently the lecherous party animals of the Middle Ages.

Some of our enduring favourites have had complex pasts. Before a ‘murmuration’ settled upon starlings (inspired by the sound of the birds when flocking together), the collective noun was ‘mutation’, thanks to the belief that the bird shed a leg at the age of ten and then promptly grew a new one. An ‘unkindness of ravens’ arose from the belief that these huge, dark carrion birds were omens of doom.

Some from the past deserve to be brought back: such as a ‘drunkenship of cobblers’, born in a time when ale was safer to drink than water. And then there are those that are surely due a revival: today’s postal workers would enjoy ‘a diligence of messengers’, while pub landlords and landladies might happily join a ‘laughter of hostelers’.

Today, there is no official list of collective nouns, and the search for new ones goes on. Modern choices, submitted whenever the topic trends (and it does, often), include a ‘foothurt of Lego’, a ‘pedant of Oxford commas’, a ‘blur of opticians’, and a ‘wunch of bankers’. The search for the name for a group of politicians goes on.

Word Perfect, Etymological Entertainment for Every Day of the Year by Susie Dent

Dutch

9 June – Dutch Feast

John Camden Hotten was one of the first and best lexicogaphers of slang. He gathered and documented what he himself described as “that evanescent, vulgar language, ever changing with fashion and taste… spoken by persons in every grade of life, rich and poor, honest and dishonest”. One result of his indefatigable quest for the language of “fast, high and low life” was the publication, in 1859, of A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words. On the day Hotten died in 1873 (of brain fever, or a surfeit of pork chops, depending on which historian you ask) he was still revising his work.

Among the back slang and rhyming slang, and the patter from sailors and shopkeepers, are such expressions as a “Dutch uncle”, defined by the author as “a person often introduced in conversation, but exceedingly difficult to describe”. A “Dutch concert” is one in which “each performer plays a different tune”, and “Dutch consolation” is simply “Thank God it’s no worse”.

These less well-known Dutch formulae sit alongside those that have endured to this day; “Dutch courage”, namely false courage garnered through drinking; “double Dutch”, i.e. gibberish; and “going Dutch”, where everyone splits the bill and thus risks the suggestion of miserliness. But why Dutch?

In the seventeenth century, the Dutch and British were at loggerheads. Both sought maritime superiority, and not least the control of the sea routes that carried exotic cargo from the rich Spice Islands of the East Indies. The result of such vying for supremacy was three naval wars between the years 1652 and 1674. On 9 June 1667, the Dutch sailed up the Medway, sank multiple British ships, and blockaded the Thames. The ensuing bitterness on the part of the British resulted in “Dutch” becoming synonymous with such unappealing qualities as cowardice and stinginess.

Today, even while most prejudice towards our friends in the Netherlands has long since vanished, a couple of contemporary examples might occasionally feel useful. A “Dtuch reckoning” is a bill that is presented without any detail and which only gets bigger if you question it, while a “Dutch feast” is one at which the host “gets drunk before the guests”.

Word Perfect, Etymological Entertainment for Every Day of the Year by Susie Dent